Exploring the Distribution and Therapeutic Potential of Medicinal Plants: Nature’s Pharmacy for Disease Treatment

| Received 27 Oct, 2024 |

Accepted 05 Dec, 2024 |

Published 31 Mar, 2025 |

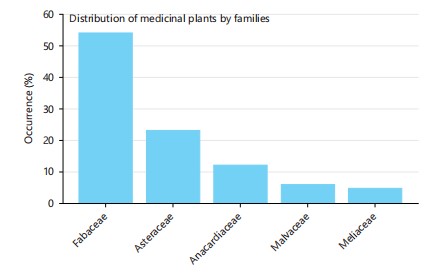

Background and Objective: Various indigenous plants are used in traditional medicine to treat ailments like malaria, infections and digestive disorders. Common plants are valued for their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. This study presents an ethnobotanical survey of the flora and medicinal plants on the University of Maiduguri Campus, Nigeria, focusing on their diversity, distribution and ethnomedicinal uses. Materials and Methods: This cross-sectional survey at the University of Maiduguri Campus, Nigeria, used purposive and snowball sampling to recruit participants knowledgeable in traditional medicine. Data collection involved structured interviews, field observations and plant sample collection. Descriptive statistics summarized participant demographics and plant usage, while Chi-square tests assessed associations between demographics and usage patterns. Analysis was conducted using SPSS with a significance level of p<0.05. Results: The survey identified a wide variety of medicinal plants, with the family Fabaceae exhibiting the highest occurrence (54.12%), followed by Asteraceae (23.01%) and Anacardiaceae (12.11%). Among the plant types, herbs were the most abundant, followed by trees and shrubs. The medicinal properties of these plants were diverse, with a notable emphasis on their anticancer properties, which were the most common, followed by antimalarial applications. The study also highlighted conservation concerns, with 8% of the identified species being endangered, including Detarium microcarpum. This survey underscores the importance of documenting and preserving the ethnobotanical knowledge of the region, particularly considering the potential therapeutic applications and the risk of biodiversity loss. Conclusion: The findings provide valuable insights into medicinal plant usage on the University of Maiduguri Campus, highlighting plant diversity and traditional applications. This documentation aids in understanding local ethnobotanical knowledge and supports future conservation.

| Copyright © 2025 Ukwubile and Gangpete. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

The University of Maiduguri, located in Northeastern Nigeria, serves as a hub of educational and cultural diversity, hosting a community that integrates traditional knowledge and modern science.

Ethnobotanical knowledge has been passed down through generations, highlighting the importance of plants in traditional healing systems. Nigeria, rich in biodiversity, is home to numerous plant species known for their therapeutic properties. Among these, members of families such as Fabaceae, Asteraceae and Anacardiaceae are commonly utilized for treating ailments ranging from infectious diseases to chronic conditions1-4. The reliance on these plants is particularly significant in rural and semi-urban settings, where access to conventional healthcare may be limited. Research on the local use of medicinal plants not only preserves indigenous knowledge but also provides insights into the pharmacological potential of these species. Documenting plants used for treating various diseases can lead to the identification of promising candidates for drug development, particularly in the realm of anticancer therapies.

Medicinal plants have long been an essential component of traditional healthcare systems around the world, serving as primary sources of therapeutic agents for treating a diverse range of ailments1. Their importance is especially evident in many developing regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, where access to modern healthcare facilities and pharmaceuticals may be limited. In such areas, indigenous communities rely heavily on plant-based remedies to manage diseases such as malaria, cancer, diabetes and various infectious and inflammatory conditions. These plants often contain bioactive compounds that have inspired the development of modern drugs, underscoring their relevance to both traditional medicine and contemporary pharmacological research2.

Nigeria, one of the most biologically diverse countries in Africa, is home to a rich array of medicinal plants and possesses a wealth of traditional knowledge related to their use. However, much of this knowledge is transmitted orally across generations, which makes it vulnerable to loss as a result of cultural shifts, urbanization, deforestation and other environmental pressures. The Northeastern Region of Nigeria, including Borno State, is a repository of various plant species with significant medicinal properties. However, ongoing challenges like desertification, armed conflicts and climate change threaten this biodiversity, creating an urgent need for systematic documentation of plant species and their uses.

Ethnobotanical surveys are critical in this context, as they help document the medicinal plants and the associated traditional knowledge before it is lost. Such surveys provide valuable insights into the cultural importance of these plants and can guide the conservation of species at risk of extinction3. Additionally, they can serve as a basis for scientific validation of traditional uses and potential pharmaceutical exploration. By identifying plants with significant medicinal properties, researchers can focus on species that may yield new, effective therapeutic agents. Despite its rich plant diversity, there is limited documentation of the medicinal plants on the campus and their potential uses. While some studies have been conducted in other parts of Nigeria, the ethnobotanical data specific to this region remain scarce, representing a significant research gap by Abd El-Ghani4.

Although previous studies have explored medicinal plant use in various parts of Nigeria, there is a lack of comprehensive ethnobotanical surveys specific to the northeastern region, particularly within the University of Maiduguri campus. This gap in knowledge limits the ability to effectively document and preserve the traditional medicinal practices of local communities, as well as to identify plant species with potential for pharmacological research5. Additionally, there is limited data on the conservation status of medicinal plants in this region, making it difficult to prioritize efforts to protect endangered species. By addressing these gaps, this study aimed to provide a detailed record of the medicinal plants in the area, their uses and their conservation status, which could be valuable for future pharmacological studies, conservation strategies and sustainable use of plant resources. Thus, the primary objective of this study is to conduct an ethnobotanical survey of the medicinal plants on the University of Maiduguri campus, Nigeria, to identify the diversity, traditional uses and conservation status of these plants. The study seeks to: Document the diversity of medicinal plants on the campus, focusing on their distribution among different families, assess the types of plant life forms present (herbs, trees, shrubs) and their relative abundance, identify medicinal plants used for treating specific health conditions, such as cancer and malaria, to highlight their ethnomedicinal significance and determine the conservation status of the recorded species, particularly those at risk of extinction, to inform future conservation efforts.

By filling the existing research gap, this study aims to contribute to the documentation of medicinal plants on the Campus, preservation of ethnobotanical knowledge and support the sustainable management of medicinal plant resources in the University of Maiduguri Campus, Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area: The ethnobotanical survey was conducted on the campus of the University of Maiduguri, located in Maiduguri, Borno State, Northeastern Nigeria. The university campus is characterized by a semi-arid climate, with a distinct wet season (June to October, 2023) and dry season (November 2023 to May 2024). The vegetation in this region consists mainly of savannah and semi-desert species, with a diverse range of herbs, shrubs and trees. This environment provides a suitable habitat for a variety of medicinal plants, which are used by local communities for traditional healthcare practices.

Survey design: The study employed a cross-sectional ethnobotanical survey design, aimed at documenting the medicinal plant species present on the university campus and gathering information on their uses from local informants. The survey was conducted from December, 2023 to November, 2024, covering different parts of the campus, including open fields, wooded areas and riparian zones along watercourses. The campus was divided into zones and plant species were sampled systematically within each zone to ensure comprehensive coverage of the area6.

Data collection

Plant sampling and identification: Plant specimens (seventy-six) were collected using a systematic random sampling method. In each zone, plots of 10×10 m were demarcated and within these plots, all visible medicinal plants were recorded. A minimum of three plots were surveyed in each zone to account for plant diversity. Fresh samples, including leaves, stems, flowers and fruits, were collected for identification. Digital photographs of the plants were taken to aid in identification and future reference7. Plant identification was carried out using local herbarium resources and reference books, as well as consultations with taxonomists at the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Maiduguri. Identification was confirmed using standard botanical keys and compared with herbarium specimens at the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Maiduguri, Nigeria.

Ethnobotanical data collection: Ethnobotanical data were collected through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions with local informants, including traditional healers, herbalists and elders from nearby communities who possess knowledge of medicinal plants. A total of twenty informants were selected using a purposive sampling method based on their knowledge and experience in traditional medicine. Interviews were conducted in the Hausa and Kanuri languages, with translation into English as needed. Informants were asked about the local names, parts used, methods of preparation and medicinal uses of each plant species. Special attention was given to plants used for treating conditions such as cancer, malaria and other prevalent diseases in the area. The conservation status of the plants, including whether they were considered endangered or overharvested, was also discussed with the informants.

Voucher specimen preparation: For each identified plant species, voucher specimens were prepared following standard herbarium procedures. The specimens were pressed, dried and mounted on herbarium sheets and labeled with information including the plant name, family, locality, date of collection and collector’s name. The prepared voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the Department of Pharmacognosy, University of Maiduguri, for future reference.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis: The relative frequency of occurrence (RFO) of each plant family was calculated as a percentage of the total number of recorded species8. The formula used for RFO is:

The abundance of different life forms (herbs, trees and shrubs) was determined by calculating their percentage occurrence relative to the total plant species documented.

Ethnobotanical use value: The use value (UV) of each medicinal plant was calculated to determine the significance of each species in traditional medicine9. The UV was calculated using the formula:

where, UV is the use value of plants, ΣUi is the number of uses mentioned by each informant for a given species and N is the total number of informants. Plants with the highest use values were considered the most important in the local ethnomedicinal context.

Conservation status assessment: The conservation status of each recorded species was evaluated using informant responses and cross-referenced with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and Relevant Regional Conservation Lists. Species identified as endangered or vulnerable by local informants were cross-checked with existing conservation data to validate their status8.

Statistical analysis: Data obtained were expressed in percentages of the total number of plants surveyed within the campus.

Ethical consideration: Not applicable because no humans or animals were experimented upon. Approval was granted to embark on a field trip with students on course code: PCG 599.

RESULTS

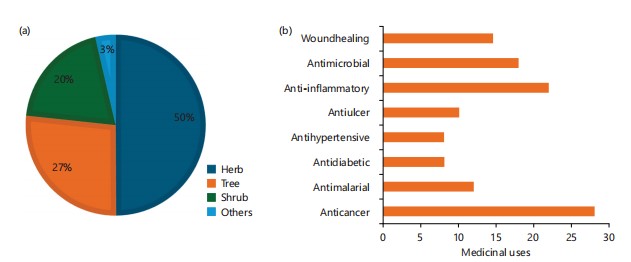

Plant species and uses: From the study, the herbs were more in number (50%) followed by the trees (27%) and shrubs (20%) and others were 3% (Fig. 1a). The anticancer plants were more in number (Fig. 1b).

Plant distribution according to mode of preparations: The study showed that most plants surveyed were prepared for medicinal use by a decoction of leaves, roots and stembarks of herbs, trees and shrubs, for certain diseases. Most of the plants’ roots are prepared for medicinal use by infusion unlike other morphological parts (Fig. 2).

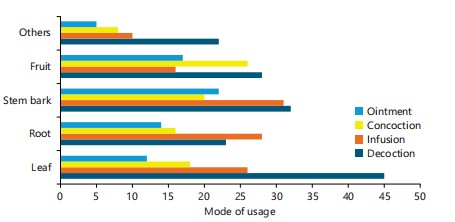

Medicinal plants and flora distribution: Table 1 shows 75 plants from various species and families and the conservation status of various medicinal plants identified in the ethnobotanical survey on the University of Maiduguri campus. The family Fabaceae was the highest in number with more species (Fig. 3). The conservation status categories typically include least concern (LC), near threatened (NT), vulnerable (VU), endangered (EN) and critically endangered (CR) according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Plants distribution: The chart (Fig. 3) illustrates the percentage of occurrence for each family, with Fabaceae having the highest representation at 54.12%, followed by Asteraceae and Anacardiaceae. This visualization effectively highlights the diversity and prevalence of different plant families in the survey.

|

|

|

Relative use of the surveyed plants: Table 2 shows the relative frequency of occurrence (RFO), use value (UV), informant consensus factor (ICF) and fidelity level (FL) for the medicinal plants in the survey. From the results, Detarium microcarpum has the highest RFO, UV, ICF and FL.

| Table 1: | Medicinal plants distribution on University of Maiduguri Campus | |||

| Plant Species | Family | Status | Major use | Voucher number |

| Ficus nymphaeifolia Mill. | Moraceae | LC | Typhoid fever, infection, diarrhea | UMM/FPH/MOA/004 |

| Azadirachta indica A. Juss. | Meliaceae | LC | Cancer, fevers, antimicrobial | UMM/FPH/MEA/001 |

| Detarium microcarpum Guill. & Perr. | Fabaceae | EN | Cancer, antioxidant, wound healing | UMM/FPH/FAA/009 |

| Ziziphus mauritiana | Rhamnaceae | NT | Hepatoprotective, cancer, diabetes | UMM/FPH/RAN/003 |

| Adansonia digitata L. | Malvaceae | NT | Antioxidant, ulcer | UMM/FPH/MAV/001 |

| Khaya senegalensis | Meliaceae | VU | Fevers, inflammation | UMM/FPH/MEA/002 |

| Ceratonia siliqua L. | Fabaceae | EN | Fevers, infection | UMM/FPH/FAA/013 |

| Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth. | Fabaceae | NT | Cancer, fever | UMM/FPH/FAA/012 |

| Terminalia arjuna (Roxb. ex-DC.) Wight & Arn. | Combretaceae | CR | Cancer, inflammation | UMM/FPH/COB/004 |

| Ficus religiosa L. | Moraceae | NT | Typhoid fever, infections, malaria, | UMM/FPH/MOA/003 |

| Gossypium herbaceum L. | Malvaceae | NT | Inflammation | UMM/FPH/MAV/010 |

| Gossypium hirsutum L. | Malvaceae | NT | Inflammation, cancers, fevers | UMM/FPH/MAV/014 |

| Leucas urticifolia (Vahl.) Sm | Lamiaceae | LC | Cancer, diabetes and wound healing | UMM/FPH/LAA/011 |

| Leucas martinicensis (Jacq.) R.Br | Lamiaceae | EN | Cancer, cough, fever | UMM/FPH/LAA/012 |

| Spigelia anthelmia L. | Asteraceae | NT | Worms, eczema, cancer | UMM/FPH/ASR/008 |

| Senna obtusifolia (L.) H.S. Irwin & Barneby | Fabaceae | LC | Fever, ulcer, cancer | UMM/FPH/FAA/018 |

| Senna tora (L.) Roxb. | Fabaceae | LC | Fever, cancer, antiviral | UMM/FPH/FAA/005 |

| Hyphaene thebaica (L.) Mart. | Arecaceae | EN | Hypertension, ulcer, sexual stimulant | UMM/FPH/ARC/001 |

| Brahea armata S. Watson | Arecaceae | NT | Purgative, cancer, diabetes | UMM/FPH/ARC/005 |

| Ficus retusa L. | Moraceae | VU | Typhoid, pains, inflammation, dysentery | UMM/FPH/MAO/006 |

| Ficus microcarpa L.f. | Moraceae | LC | Hyperlipidemia, hepatoprotective | UMM/FPH/MAO/007 |

| Monoon longifolium (Sonn.) B.Xue | Annonaceae | VU | Cancer, diabetes, fevers, convulsion | UMM/FPH/ANO/001 |

| Annona senegalensis Pers. | Annonaceae | EN | Cancer, inflammation, pains, fevers | UMM/FPH/ANO/003 |

| Ziziphus jujuba Mill | Rhamnaceae | LC | Hepatoprotective, diabetes, ulcer | UMM/FPH/RAN/018 |

| Ziziphus lotus Lam. | Rhamnaceae | EN | Hepatoprotective, cancer, fever, wound healing | UMM/FPH/RAN/008 |

| Ziziphus mauritiana Lam. | Rhamnaceae | LC | Wound healing, antiviral, diarrhea | UMM/FPH/RAN/003 |

| Cynanchum acutum L. | Apocynaceae | CR | Cancer, hepatitis, hypotension | UMM/FPH/APN/010 |

| Leptadenia hastata Pers | Apocynaceae | NT | Diabetes, sexual drive, pains | UMM/FPH/APN/003 |

| Laggera crispata (Vahl.) Hepper | Asteraceae | VU | Cancer, cough, hypertension | UMM/FPH/MEA/020 |

| Crepis pulchra L. | Asteraceae | EN | Cancer, inflammation, antioxidant | UMM/FPH/ASR/022 |

| Heliotropium europaeum L. | Boraginaceae | CR | Cancer, tumor, wound healing | UMM/FPH/BOG/004 |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Myrtaceae | EN | Inflammation, rheumatism, purgative | UMM/FPH/MYT/001 |

| Balanites aegyptiaca | Zygophyllaceae | EN | Diabetes, ulcer, insomnia | UMM/FPH/ZYO/001 |

| Phoenix reclinata Jacq. | Arecaceae | LC | Diabetes, cardiotonic, sexual drive | UMM/FPH/ARC/003 |

| Phoenix dactylifera L. | Arecaceae | EN | Diabetes, ulcer, hypertension | UMM/FPH/ARC/002 |

| Aleo officinalis Forssk. | Asphodelaceae | CR | Infections, fevers, ulcer | UMM/FPH/ASH/004 |

| Aleo vera (L.) Burm.f | Asphodelaceae | CR | Infection, purgative, antioxidant | UMM/FPH/ASH/002 |

| Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | Myrtaceae | EN | Inflammatory, analgesics, ulcer | UMM/FPH/MYT/002 |

| Terminalia mantaly H. Perrier | Combretaceae | NT | Ulcer, cancer, hepatoprotective | UMM/FPH/COB/001 |

| Citrus × aurantiifolia (Chistm.) Swingle | Rutaceae | LC | Antioxidant, ulcer, purgative | UMM/FPH/RUT/005 |

| Citrus × limon (L.) Osbeck | Rutaceae | LC | Antioxidant, infection, cardiotonic | UMM/FPH/RUT/001 |

| Senna siamea (Lam.) H.S. Irwin & Barneby | Fabaceae | NT | Cancer, antitumor, hepatoprotective | UMM/FPH/FAA/023 |

| Synedrella nodiflora (L.) Gaertn. | Asteraceae | LC | Cancer, worms, fungi, infection | UMM/FPH/ASR/022 |

| Sesbania herbacea (Mill.) McVaugh | Fabaceae | CR | Cancer, inflammation, diabetes | UMM/FPH/FAA/024 |

| Mangifera indica L. | Anacardiaceae | LC | Fever, ulcer, dysentery, infection | UMM/FPH/ANC/001 |

| Cucurbita maxima Duch. | Cucurbitaceae | LC | Diabetes, purgative, cancer, antioxidant | UMM/FPH/CUB/003 |

| Momordica balsamina L. | Cucurbitaceae | CR | Cancer, hepatoprotective, insomnia | UMM/FPH/CUB/001 |

| Achyranthes aspera L. | Amaranthaceae | VU | Worm, cancer, sexual tonic, inflammation | UMM/FPH/ASH/004 |

| Jatropha curcas L. | Euphorbiaceae | NT | Anti-inflammatory, cancer, worm, infection, fevers | UMM/FPH/EUB/004 |

| Euphorbia hirta L. | Euphorbiaceae | VU | Cancer, antiviral, asthma, rashes, infections | UMM/FPH/EUB/001 |

| Calotropis procera Aiton | Apocynaceae | LC | Ring worm, kidney problem, rashes | UMM/FPH/APN/002 |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Wild. | Fabaceae | NT | Cancer, inflammation, purgative, ulcer, diabetes | UMM/FPH/FAA/003 |

| Adansonia digitata L. | Malvaceae | VU | Ulcer, fever, worm, cholesterol reduction | UMM/FPH/MAV/001 |

| Sterculia setigera Del. | Malvaceae | CR | Inflammation, cancer, antioxidant | UMM/FPH/MAV/008 |

| Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd. | Nyctaginaceae | VU | Hepatoprotective, fever, cancer | UMM/FPH/NYG/001 |

| Bidens pilosa L. | Asteraceae | LC | Worms, cancer, cholesterol | UMM/FPH/ASR/006 |

| Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth | Bignoniaceae | CR | Cancer, antioxidant, analgesics | UMM/FPH/BIN/003 |

| Bauhinia reticulata DC. | Fabaceae | NT | Cancer, inflammation, pains | UMM/FPH/FAA/022 |

| Morus indica L. | Moraceae | CR | Cancer, ulcer, aphroditic | UMM/FPH/MOA/011 |

| Solanum americanum Mill. | Solanaceae | CR | Inflammation, antioxidant, immune boast | UMM/FPH/SON/003 |

| Cnidoscolus chayamansa McVaugh | Euphorbiaceae | CR | Cancer, antioxidant, blood boast, inflammation, fevers | UMM/FPH/EUB/003 |

| Datura innoxia Mill. | Solanaceae | LC | Cancer, anxiolytic, pains | UMM/FPH/SON/001 |

| Ricinus communis L. | Euphorbiaceae | VU | Cancer, inflammation, purgative, fevers | UMM/FPH/EUB/024 |

| Cassia fistula L. | Fabaceae | VU | Inflammation, cancer, purgative | UMM/FPH/FAA/007 |

| Faidherbia albida (Delile) A. Chev. | Fabaceae | LC | Cancer, purgative, inflammation, fever, toothache | UMM/FPH/FAA/015 |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | Malvaceae | NT | Hypertension, cardiac stimulant, immune boost | UMM/FPH/MAV/002 |

| Crotalaria pallida Aiton | Fabaceae | LC | Immune boost, pains, fevers | UMM/FPH/FAA/025 |

| Pongamia pinnata (L.) Pierre | Fabaceae | CR | Cancer, wound healing, pains | UMM/FPH/FAA/026 |

| Helianthus annuus L. | Asteraceae | VU | Cancer, cholesterol, worms | UMM/FPH/ASR/018 |

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | Simaroubaceae | CR | Hypertension, antidiabetic, pains, cancer | UMM/FPH/SIB/001 |

| Corchorus olitorius L. | Malvaceae | LC | Hypertension, inflammation, aphroditic | UMM/FPH/MAV/031 |

| Indigofera tinctoria L. | Fabaceae | VU | Cancer, diabetes, hepatoprotective | UMM/FPH/FAA/034 |

| Piliostigma thonningii (Schum.) Milne-Redh | Fabaceae | NT | Cancer, tumor, diabetes | UMM/FPH/FAA/030 |

| Cryptostegia madagascariensis Bojer ex Dence | Apocynaceae | CR | Cancer, ulcer, pains, sperm boosting | UMM/FPH/APN/001 |

| Mesosphaerum suaveolens (L.) Kuntze | Lamiaceae | EN | Cancer, antipyretic, ulcer, diarrhea | UMM/FPH/LAA/015 |

| LC: Least concern, NT: Near threatened, VU: Vulnerable, EN: Endangered and CR: Critically endangered | ||||

| Table 2: | Relevance of medicinal plants surveyed according to surveyed parameters | |||

| Plant species | RFO (%) | UV | ICF | FL (%) | Major ailments treated |

| Heliotropium europaeum | 8.2 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 65 | Anticancer, antidiabetic, antimalarial |

| Azadirachta indica | 7.5 | 0.68 | 0.8 | 55 | Antimalarial, antipyretic, antibacterial |

| Ziziphus lotus | 6.4 | 0.55 | 0.78 | 60 | Anticancer, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective |

| Detarium microcarpum | 18.04 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 84 | Anticancer, antihypertensive |

| Ziziphus mauritiana | 4.8 | 0.48 | 0.7 | 50 | Antidiabetic, liver injuries, anti-inflammatory |

| Annona senegalensis | 4.5 | 0.6 | 0.82 | 68 | Antimicrobial, wound healing |

| Euphorbia hirta | 4.2 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 40 | Antimalarial, hepatoprotective |

| Pongamia pinnata | 3.8 | 0.52 | 0.77 | 58 | Anticancer, inflammation, immune booster |

| Khaya senegalensis | 3.2 | 0.42 | 0.6 | 45 | Antimalarial, hepatoprotective, antipyretic |

| Indigofera tinctoria | 2.9 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 52 | Anticancer, antidiabetic |

| RFO: Relative frequency of occurrence, UV: Use value, ICF: Informant consensus factor and FL: Fidelity level | |||||

DISCUSSION

The results reveal that the Fabaceae family is the most prominent, representing 54.12% of the documented species. This finding corroborated previous research indicating that Fabaceae plants are rich in phytochemicals, which are essential for various medicinal applications8. The diversity within this family, including species like Ziziphus lotus and Detarium microcarpum, underlines their importance not only in traditional medicine but also in potential pharmaceutical development.

The survey’s findings emphasize the predominance of herbs over trees and shrubs, suggesting that local communities favor species that are easily accessible and can be cultivated without extensive resources9. The identification of leaf decoction as the primary method of preparation underscores traditional practices rooted in the community’s cultural heritage. This method’s popularity reflects a blend of convenience and effectiveness, allowing for the easy extraction of active compounds from plant materials10. In terms of medicinal uses, the study highlights that anticancer and antimalarial plants are most frequently cited, indicating a pressing need for effective treatments against these prevalent health issues in Nigeria11. The high incidence of cancer and malaria underscores the relevance of the survey findings in addressing public health challenges12. Moreover, the diversity of reported medicinal uses, including antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective properties, suggests that the local flora could serve as a valuable resource for drug discovery.

The assessment of the conservation status of the plants reveals alarming trends, particularly regarding endangered species like Detarium microcarpum. The overharvesting of these plants, coupled with habitat destruction due to urbanization and agricultural expansion, poses a serious threat to their survival13. The presence of endangered species within the community’s medicinal repertoire highlights the urgent need for sustainable practices and conservation efforts. Furthermore, the informant consensus factor (ICF) and fidelity level (FL) scores demonstrate a high level of agreement among informants regarding the therapeutic uses of specific plants9. This consensus is crucial as it validates the efficacy of these plants in traditional medicine and emphasizes the importance of preserving indigenous knowledge6. It also points to the potential for collaborative research that integrates traditional practices with scientific exploration, providing a holistic approach to medicinal plant studies14.

Finally, the ethnobotanical survey conducted at the University of Maiduguri underscores the rich diversity and cultural significance of medicinal plants within the university community. The predominance of the Fabaceae family- A group known for its numerous species with valuable medicinal properties-illustrates not only the variety of available resources but also the deep-rooted traditional practices that involve these plants15. The survey reveals a wide array of medicinal uses, ranging from treatments for common ailments to more complex therapeutic applications, demonstrating how integral these plants are to the health and well-being of the community. Furthermore, the reliance on traditional preparation methods reflects an ancestral knowledge system that has been passed down through generations, indicating a profound

connection between the community and its natural environment. Such practices are often rooted in cultural beliefs and local customs, emphasizing the importance of preserving this knowledge as a vital aspect of cultural heritage16. However, the identification of endangered species within the study highlights a critical concern for biodiversity and sustainability. The threats posed by habitat loss- due to urbanization, agricultural expansion and climate change and the practice of overharvesting for medicinal use threaten not only the survival of these species but also the traditional health practices that rely on them. This situation necessitates urgent conservation action to protect these plants and their habitats. Conservation efforts should focus on raising awareness about the importance of these medicinal plants and promoting sustainable harvesting practices6. Additionally, integrating the knowledge from the community with scientific research can lead to the formulation of effective conservation strategies. Engaging local community members in conservation initiatives can foster stewardship over their natural resources, ensuring both the preservation of biodiversity and the continuation of traditional medicinal practices for future generations16. Thus, the survey not only serves as a documentation of existing practices but also as a call to action to safeguard these invaluable natural resources.

CONCLUSION

This study documents valuable plant resources and calls for sustainable practices to balance the demand for medicinal plants with biodiversity preservation. It highlights the importance of integrating traditional knowledge with scientific research to foster innovative healthcare solutions. Further research is necessary to explore the phytochemical properties and therapeutic potentials of these plants. Collaborations among ethnobotanists, pharmacologists and local healers can lead to new drug development and improved bioprospecting efforts. Establishing a centralized database of medicinal plants on campus-detailing their uses, conservation status and potential threats-would be beneficial for future research and conservation. By implementing these recommendations, the University of Maiduguri and its communities can promote sustainable use and conservation of medicinal plants, contributing to biodiversity conservation and enhancing local health and well-being for a sustainable future.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The ethnobotanical survey on medicinal plants at the University of Maiduguri, Nigeria, serves multiple purposes. It documents and preserves indigenous knowledge on plant-based treatments, crucial to local healthcare practices and culture. The study provides insights into plants with potential pharmacological benefits, possibly leading to new drug discoveries for global health challenges. It also underscores the importance of biodiversity conservation by showcasing the medicinal value of local flora and the need to protect these resources. This research fosters collaboration among researchers, traditional practitioners and policymakers, enhancing public health approaches and laying the foundation for future studies on plant-based medicine in areas with limited healthcare resources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the University of Maiduguri Management and University of Maiduguri Campus community and the 500 L (B. Pharm students 2024) for every assistance given in this study.

REFERENCES

- Armansyah, T., T.N. Siregar, Suhartono and A. Sutriana, 2022. Phytochemicals, characterization and antimicrobial tests of red betel leaves on three solvent fractions as candidates for endometritis phytotherapy in Aceh Cattle, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Diversity, 23: 2111-2117.

- Oborirhovo, O., A.A. Anigboro, O.J. Avwioroko, O. Akeghware, B.J. Okafor, F.O. Ovowa and N.J. Tonukari, 2023. GC-MS characterized bioactive constituents and antioxidant capacities of aqueous and ethanolic leaf extracts of Rauvolfia vomitoria: A comparative study. Niger. J. Sci. Environ., 2: 479-499.

- Murtala, A.A. and A.J. Akindele, 2020. Anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like activities of hydroethanol leaf extract of Newbouldia laevis (P.Beauv.) Seem. (Bignoniaceae) in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol., 249.

- Abd El-Ghani, M.M., 2016. Traditional medicinal plants of Nigeria: An overview. Agric. Biol. J. North Am., 7: 220-247.

- Atawodi, S.E.O., O.D. Olowoniyi and M.A. Daikwo, 2014. Ethnobotanical survey of some plants used for the management of hypertension in the igala speaking area of Kogi State, Nigeria. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol., 4: 4535-4543.

- Hassan, I.M., A. Shehu, A.U. Zezi, M.G. Magaji and J. Ya’u, 2020. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants commonly used in snakebites in North Western Nigeria. J. Med. Plants Res., 14: 468-474.

- Shrestha, P.M. and S.S. Dhillion, 2003. Medicinal plant diversity and use in the highlands of Dolakha District, Nepal. J. Ethnopharmacol., 86: 81-96.

- Nondo, R.S.O., D. Zofou, M.J. Moshi, P. Erasto and S. Wanji et al., 2015. Ethnobotanical survey and in vitro antiplasmodial activity of medicinal plants used to treat malaria in Kagera and Lindi Regions, Tanzania. J. Med. Plants Res., 9: 179-192.

- Yemane, B., G. Medhanie and K.S. Reddy, 2017. Survey of some common medicinal plants used in Eritrean folk medicine. Am. J. Ethnomed., 14.

- Odebunmi, C.A., T.L. Adetunji, A.E. Adetunji, A. Olatunde and O.E. Oluwole et al., 2022. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the treatment of COVID-19 and related respiratory infections in Ogbomosho South and North Local Government Areas, Oyo State, Nigeria. Plants, 11.

- Bencheikh, N., A. Elbouzidi, L. Kharchoufa, H. Ouassou and I.A. Merrouni et al., 2021. Inventory of medicinal plants used traditionally to manage kidney diseases in North-Eastern Morocco: Ethnobotanical fieldwork and pharmacological evidence. Plants, 10.

- Koubi, Y., H. Hajji, Y. Moukhliss, K. El Khatabi and Y. El Masaoudy et al., 2022. In silico studies of 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole with amide functionality antimicrobial evaluation against Escherichia coli using 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and ADMET properties. Moroccan J. Chem., 10: 689-702.

- Dogara, A.M., 2022. Biological activity and chemical composition of Detarium microcarpum Guill. and Perr-A systematic review. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci., 2022.

- Tamilselvan, N., T. Thirumalai, P. Shyamala and E. David, 2014. A review on some poisonous plants and their medicinal values. J. Acute Dis., 3: 85-89.

- Manikandaselvi, S., V. Vadivel and P. Brindha, 2016. Review on nutraceutical potential of Cassia occidentalis L.-An Indian traditional medicinal and food plant. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 37: 141-146.

- Rahman, I.U., R. Hart, A. Afzal, Z. Iqbal and F. Ijaz et al., 2019. A new ethnobiological similarity index for the evaluation of novel use reports. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res., 17: 2765-2777.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Ukwubile,

C.A., Gangpete,

S.I. (2025). Exploring the Distribution and Therapeutic Potential of Medicinal Plants: Nature’s Pharmacy for Disease Treatment. Asian Journal of Biological Sciences, 18(1), 195-205. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2025.195.205

ACS Style

Ukwubile,

C.A.; Gangpete,

S.I. Exploring the Distribution and Therapeutic Potential of Medicinal Plants: Nature’s Pharmacy for Disease Treatment. Asian J. Biol. Sci 2025, 18, 195-205. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2025.195.205

AMA Style

Ukwubile

CA, Gangpete

SI. Exploring the Distribution and Therapeutic Potential of Medicinal Plants: Nature’s Pharmacy for Disease Treatment. Asian Journal of Biological Sciences. 2025; 18(1): 195-205. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2025.195.205

Chicago/Turabian Style

Ukwubile, Cletus, Anes, and Semen Ibrahim Gangpete.

2025. "Exploring the Distribution and Therapeutic Potential of Medicinal Plants: Nature’s Pharmacy for Disease Treatment" Asian Journal of Biological Sciences 18, no. 1: 195-205. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2025.195.205

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.