Pharmacological Potential of Cocos nucifera L. Flowers: Phytochemical, Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Anthelmintic and Anti-Diabetic Insights

Background and Objective: Cocos nucifera L. flowers, a less-researched component, have been identified as promising therapeutic components, yet their pharmacological profile remains insufficiently understood. This study investigates the phytochemical and pharmacological properties of the flower extract, focusing on its antioxidant, antimicrobial and antidiabetic properties.Materials and Methods: Cocos nuciferaflowers of methanolic extract were prepared and subjected to a comprehensive phytochemical assay, including the identification of total phenolic contents. Antioxidant activity was determined using DPPH radical scavenging and reducing power assays; however, the extract’s cytotoxicity, anthelmintic and α-amylase inhibitory effects were examined using standard bioassay techniques. Results: The phytochemical analysis demonstrates key bioactive compounds, including alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins and reducing sugars. The flower extract reveals considerable antioxidant activity, compared to higher concentrations of ascorbic acid. The cytotoxicity screening indicates moderate toxicity (LC50 = 40.59 μg/mL), though the α-amylase inhibition test showed 65.75% inhibition at 0.5 mg/mL, suggesting prospective antidiabetic effects. On the other hand, the anthelmintic activity of the extract was less potent than the standard drug albendazole, yet it exhibits some degree of efficacy. Conclusion: The study indicates that Cocos nucifera flowers contain some valuable bioactive properties, revealing promising antioxidant, antidiabetic and cytotoxic properties. Findings of the research highlight the unexplored therapeutic potential of coconut flowers, probably a foundation for further investigation of their chemical constituents. Further research may focus on isolating these properties and exploring in vivo efficacy to develop novel therapeutic agents for treating diseases related to oxidative stress, metabolic disorders and microbial infections.

| Copyright © 2026 Al-Amin et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, researchers are exploring new therapeutic agents from natural sources. Historically, medicinal plants have been considered valuable ingredients for medicine research, providing numerous compounds with numerous biological properties1. Cocos nucifera L. (coconut palm) has drawn attention for its nutritional and economic importance, besides its therapeutic medicinal characteristics2,3.

Cocos nucifera, commonly known as the coconut palm, is a multidimensional crop with various applications for humankind4. Cocos nucifera is widely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions and its various parts have been identified for their nutritional and medicinal use5. Currently, the fruit, water, oil and husk, the flowers of Cocos nucifera, have been placed in focus and remain relatively undiscovered in terms of their pharmacological potential3.

For centuries, plants have been used in traditional medicine to cure various diseases, including Cocos nucifera. These plants serve as an exceptional source of phytochemicals, many of which show potent antioxidant activities, thereby contributing to the prevention and treatment of different illnesses6. The antioxidant capabilities of these substances are important because of their role in alleviating diseases related to oxidative stress7. Cocos nucifera, belonging to the Arecaceae family, is recognized for its many health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-tumor and antihypertensive qualities3,8. The medicinal properties have raised increasing scientific curiosity in the pharmaceutical potential of the Cocos nucifera (coconut palm).

In various traditional medicinal applications, the coconut palm has been utilised and its flowers have been said to help treat diseases like diarrhoea, dysentery and diabetes8. However, with its widespread uses, much of the pharmacological research on Cocos nucifera has focused on its water and fruit, with limited attention given to its flowers9. The flowers of it, mostly thrown away as waste, may carry useful biological components with potential medicinal applications10. Recent research has identified that the flowers of Cocos nucifera contain a number of bioactive components, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids, cardiac glycosides and phenolic compounds11.

Natural products have global interest, particularly when it comes to fighting against antimicrobial resistance and finding alternative treatments. Herbal medicine plays a pivotal role in the healthcare sector in South Asia, particularly in Bangladesh, especially in rural areas where modern medical facilities are very hard to access. Around 80% of the people in the world use herbal medicine for their primary healthcare12 and Bangladesh has a rich biodiversity and many of the plants and herbs in it have been documented for their medicinal purposes13-15. However, there is not enough scientific evidence that many of its traditional cures remain insufficient, indicating extensive research is needed.

This research seeks to address this gap by analyzing the phytochemical composition and pharmacological properties of Cocos nucifera L. flowers to find bioactive chemicals and evaluate their therapeutic potential through a systematic phytochemical screening and pharmacological assessment of methanol extract.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of plant and identification: Initially, a comprehensive literature review led to the choice of Cocos nucifera L. flowers from the Arecaceae family for this study. The plant flowers were collected from Jahangirnagar University, Bangladesh, in April, 2024 and identified by a taxonomist at the National Herbarium of Bangladesh, Mirpur, Dhaka.

Preparation of plant material: The sample was kept under a sunshade for 1-2 weeks and then oven dried at below 40°C for a few hours. After drying the sample, it was ground thoroughly into powder form by a grinder (Wuhu motor factory, China), which was then stored in a sealed container with a marking for identification and kept in a cool, dark and dry place for examination.

Extraction procedure: The Soxhlet device extracted 200 g of powdered flowers at 65°C in 500 mL of Methanol. Drying and soaking the powdered materials in 1 L of distilled water, followed by the methanol extract. The powders were kept in water for 7 days in a sealed container with occasional shaking and stirring. The extract was filtered through a fresh cotton bed. The filtrates were dried at 40±2°C to prepare a viscous concentration of crude extract16.

Reagents and chemicals: The following analytical-grade reagents and chemicals were used in the study from the Department of Pharmacy: Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was purchased from Merck, Sodium carbonate was supplied by E. Merck Limited, Methanol (analytical grade) was purchased from Merck and Gallic acid was purchased from Sigma Chemicals by the university authority.

Phytochemical screening: Crude flower extracts were subjected to a series of qualitative phytochemical assays to identify the presence of bioactive constituents, as indicated by characteristic color changes following standard protocols17-19.

Test for carbohydrates

Molisch’s test: A few drops of alcoholic α-naphthol solution were added to 2 mL of the extract, followed by concentrated sulfuric acid. A violet ring at the junction indicated carbohydrates20.

Fehling’s test: 1 mL each of Fehling’s solutions A and B was mixed with 2 mL of extract, then boiled. The green color precipitate indicates reducing sugars.

Test for saponins

Na2CO3 test: The 5 mL of extract was added to a drop of sodium carbonate, then shaken vigorously and rested for 5 min. Foam formation confirmed saponins. Foam Test: 1 mL of extract is mixed and shaken with water. After 1-2 min, a stable 1 cm foam layer formed, indicating the presence of saponins.

Test for flavonoids

Alkaline reagent test: The 2 mL of extract was added to Sodium hydroxide. A yellow color that turned colorless upon adding Hydrochloric Acid (HCL) confirmed flavonoids.

HCl test: Adding a few drops of strong HCl to the extract showed a yellow color, indicating flavonoids.

Test for tannins and phenolic compounds: A red color with acetic acid indicated tannins and phenols.

FeCl3 test: The 10 mL of distilled water was mixed with 5 mL of extract, then FeCl3 (5%) was added. A greenish-black precipitate confirmed tannins and phenols.

Test for alkaloids

Mayer’s test: A few drops of Mayer’s reagent were added to 1 mL of extract. A yellowish or white precipitate showed the presence of alkaloids.

Hager’s test: The 0.1 mL of picric acid solution added to 1 mL of extract produced a yellow precipitate, confirming alkaloids.

Determination of cytotoxicity

Brine shrimp lethality assay (BSLA): The Brine Shrimp Lethality Assay (BSLA) with Artemia salina Leach (brine shrimp) as the test organism, to see how lethal the plant extract was to the test organism. Brine shrimp cysts were hatched (Ocean 90, USA) in artificial seawater (38 g NaCl/L distilled water, pH 8.5, corrected with 8.2 mL of 1 N NaOH) and kept aerated for 48 hrs to obtain nauplii21.

Nine different concentrations of the plant extract were made, ranging from 320 to 1.25 μg/mL, by serial dilution in Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO). Each concentration (60 μL) was added to 5 mL of seawater in test tubes, along with 10 nauplii. For 24 hrs, the test tubes were kept under continuous lighting at room temperature.

Vincristine sulfate (20 μg/mL) functioned as the positive control, with serial dilutions extending to 0.039 μg/mL. The DMSO (30 μL) served as the negative control. The number of surviving nauplii was counted after 24 hrs. Mortality was defined as the loss of both internal and external movements for several seconds. During the test, no food was provided to the larvae to ensure mortality was due to the bioactive compounds rather than starvation22.

Data analysis: The lethal concentrations to kill 50% (LC50) and 90% (LC90) of the test organisms were calculated based on mortality percentages. These values were used to assess the relative cytotoxicity of the plant extract in comparison to the reference drug, vincristine sulfate.

Anthelmintic activity: The anthelmintic efficacy of the crude methanolic extract of Cocos nucifera was identified by using a modified method by Ajaiyeoba et al.23. Adult Pheretima posthuma (earthworms), which exhibit human intestinal roundworm parasites24, were used as the test organism.

The extract was evaluated at concentrations of 50 and 100 mg/mL, with albendazole (25 mg/mL) as a positive control. Paralysis was characterized as the inability to respond when transferred to normal saline, while death was indicated by cessation of movement and body pallor.

Pheretima posthuma were collected from the soil of Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka and cleaned with saline solution to remove any dirt. The worms (4-6 cm in length, 0.2-0.3 cm in diameter) were randomly divided into 4 groups (6 worms/group) and treated with 20 mL of the respective formulation. The first group received normal saline (negative control), the second group received Cocos nucifera methanolic extract (50 and 100 mg/mL), third group received albendazole (25 mg/mL). Extract preparations included dissolving the crude methanolic extract of Cocos nucifera in 1% DMF in saline. Albendazole was mixed in 1% DMF in saline at 25 mg/mL.

Paralysis was recorded when no movement occurred after mechanical stimulation and death was indicated by the absence of movement after vigorous shaking or dipping in warm water (~50°C), followed by body decolorization.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory effect: Alpha-amylase plays a crucial role in polysaccharide breakdown and is a key enzyme in the digestive process25. Inhibition of this enzyme is a potential strategy to manage postprandial blood glucose. The α-amylase inhibition activity was assessed using the starch-iodine method.

Phosphate buffer (0.02 M, pH 7.0, 0.006 M NaCl): A 0.02 M Na2HPO4 and NaH2PO4 mixture was prepared and adjusted to pH 7.0 with Na2HPO4 and NaH2PO4. NaCl was added to achieve a 0.006 M final concentration.

| • | α-Amylase solution: A 10 mg/mL stock solution of α-amylase was prepared in distilled water | |

| • | Starch solution (1%): Prepared by dissolving 0.1 g starch in 10 mL of distilled water and boiling | |

| • | Iodine solution (1%): Prepared by dissolving 0.1 g iodine in 10 mL of distilled water. f Phyllanthus |

To each test tube, 1 mL of plant extract (at 2, 1 and 0.5 mg/mL) or standard was added, followed by 20 μL of α-amylase solution. After 10 minutes of incubation at 37°C, 200 μL of 1% starch solution was added and incubated for another hour at 37°C. Then, 200 μL of 1% iodine solution was added and the final mixture was diluted to 10 mL with distilled water. Absorbance was measured at 565 nm. Control and blank samples were included and all tests were performed in duplicate.

Calculation of α-amylase inhibition: The percentage of α-amylase inhibition was calculated using the following formula26,27:

|

Where:

| SA | = | Absorbance of sample | |

| CA | = | Absorbance of control |

The IC50 value was calculated by plotting the percentage inhibition against the concentrations of the plant extract or standard using linear regression.

RESULTS

Preliminary phytochemical group tests: The initial phytochemical analysis of the crude aqueous extract of Cocos nucifera (CN) flowers confirmed the presence of Carbohydrates and reducing sugars. Alkaloids were identified in moderate quantities, as noted in the “++” sign, suggesting that they are a significant component of the extract. Flavonoids were also identified, though in smaller amounts, as shown by the “+” sign. Additionally, the presence of tannins and saponins was established (Table 1).

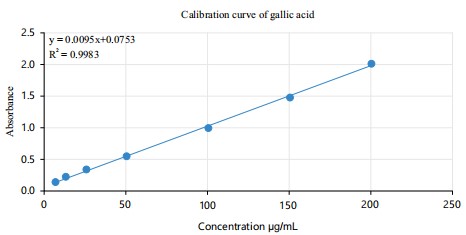

Total phenol content determination: Total phenolic content of Cocos nucifera L. flowers was measured by using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and reported as Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE). A calibration curve represented by the equation y = 0.009x+0.075, y = 0.009x+0.075, y = 0.009x+0.075 and (R² = 0.998) was established to correlate absorbance with concentration (Fig. 1). The absorbance values at 200 μg/mL for the replicates were 0.289, 0.278 and 0.299, which correspond to phenolic concentrations of 25.666, 24.444 and 26.777 mg/g, respectively. The average phenolic content across replicates was 25.629 mg/g, with a standard deviation of 1.167 (Table 2). These results indicate that Cocos nucifera flowers have a significant phenolic content, which indicates potential antioxidant activity.

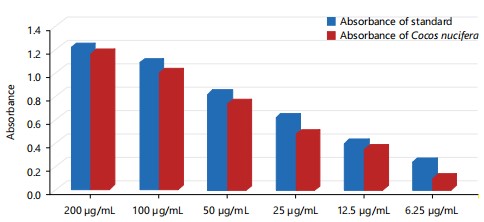

Reducing power screening: The ferric to ferrous reduction activity measured the reducing power of Cocos nucifera L. flowers, as shown in Fig. 2. The extract exhibited moderate reducing power, with higher concentrations (200 and 100 μg/mL) exhibiting absorbance values comparable to the standard. At lower concentrations (50 to 6.25 μg/mL), the reducing power of the extract gradually decreased. However, this indicates a moderate antioxidant potential of the flower extracts.

DPPH radical scavenging assay: The result of the screening was presented as a percentage of the DPPH free radical’s scavenging activity.

| Table 1: | Phytochemical analysis of the extract of Cocos nucifera (CN) flowers, indicating the presence of multiple bioactive compounds where “+” indicates presence, “++” indicates moderate presenc | |||

| Extract | Carbohydrate | Reducing sugar | Alkaloid | Flavonoid | Tannin | Saponin |

| Cocos nucifera (CN) flowers | + | + | ++ | + | + | + |

| Table 2: | Total phenolic content of Cocos nucifera L. flowers, quantified as gallic acid equivalents (GAE), along with the mean and standard deviation for three replicates | |||

| No. | Concentration (μg/mL) |

Absorbance | M = wt of plant extract |

C (mg/mL) | C (mg/mL) | C×V (mg) | A = (C×V)/M | Mean | Standard deviation |

| A | 200 | 0.289 | 0.001 | 25.666 | 0.0256 | 0.0256 | 25.666 | ||

| B | 200 | 0.278 | 0.001 | 24.444 | 0.0244 | 0.0244 | 24.444 | 25.629 | 1.167 |

| C | 200 | 0.299 | 0.001 | 26.777 | 0.267 | 0.0267 | 26.777 | ||

| M represents the weight of the plant extract (0.001 g), C (mg/mL) is the concentration of phenolics calculated using a gallic acid standard calibration curve. C×V (mg) is the product of concentration and volume of extract used (V = 1.0 mL). A = (C×V)/M expresses the total phenolic content in mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per g of extract. Values are reported as the mean of three replicates (A-C), with standard deviation indicating variability | |||||||||

|

|

|

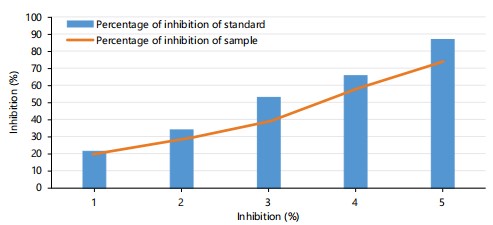

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of Cocos nucifera L. flower extract was examined and compared to a standard (Ascorbic Acid). Sample and standard both exhibited dose-dependent increases in inhibition. At higher concentrations, the extract’s inhibition approached that of ascorbic acid, achieving around 80% inhibition at the highest concentration. At lower concentrations, ascorbic acid showed slightly higher inhibition than the flower extract (Fig. 3). The results demonstrated that Cocos nucifera L. flower extract contains notable antioxidant activity, which is comparable to the standard at higher doses.

| Table 3: | Cocos nucifera L. flower extract cytotoxicity on brine shrimp nauplii with corresponding mortality rates and calculated LC50 | |||

| Conc. | Log conc. | Total shrimp | Live shrimp | Dead shrimp | Mortality (%) |

| 200 | 2.30103 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 70 |

| 100 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 60 |

| 50 | 1.69897 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 50 |

| 25 | 1.39794 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 40 |

| 12.5 | 1.09691 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 30 |

| 6.25 | 0.79588 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 30 |

| 3.125 | 0.49485 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 20 |

| 1.5625 | 0.19382 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 20 |

| 0.78125 | -0.10721 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.39063 | -0.40824 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| C50 = 40.59 μg/mL | |||||

| Table 4: | Anthelmintic activity of Cocos nucifera flower extract at various concentrations, compared to a vehicle control (BSI) and standard drug albendazole (SSI, 25 mg/mL), C1SI, C2SI = test samples | |||

| Code no. | Treatment | Time taken for paralysis (min) | Time taken for death (min) |

| BSI | Vehicle | 33.0±0.194* | 55.0±0.194* |

| SSI | 25 mg/mL | 7.30±0.194* | 10.0±0.00 |

| C1SI | 50 mg/mL | 42.0±1.378 | 60.0±0.00 |

| C2SI | 100 mg/mL | 30.0±1.14 | 63.0±0.00 |

| *p<0.001 | |||

| Values are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) for each group (n = 3), *p<0.001 indicates a statistically significant difference in comparison to the vehicle control (BSI), based on ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis | |||

| Table 5: | α-Amylase inhibition by acarbose at 2, 1, and 0.5 mg/mL (IC50 = 1.51 μg/mL) | |||

| Concentration (μg/mL) | Absorbance of acarbose | Control of acarbose | Inhibition (%) |

| 2 | 0.18 | 0.438 | 58.9 |

| 1 | 0.26 | 0.438 | 40.64 |

| 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.438 | 24.66 |

| IC50 = 1.51 μg/mL | |||

| IC50 refers to the concentration of acarbose required to inhibit 50% of α-amylase activity and μg/mL = micrograms per milliliter | |||

| Table 6: | α-Amylase inhibition by C. nucifera flower extract at 2, 1, and 0.5 mg/mL (IC50 ≈ 0.55 μg/mL) | |||

| Concentration (μg/mL) | Absorbance of plant extract | Control of plant extract | Inhibition (%) |

| 2 | 0.15 | 0.438 | 65.75 |

| 1 | 0.21 | 0.438 | 52.05 |

| 0.5 | 0.29 | 0.438 | 33.79 |

| IC50 ≈ 0.94 μg/mL | |||

| IC50 represents the concentration of the plant extract required to inhibit 50% of α-amylase activity and μg/mL = micrograms per milliliter | |||

Brine shrimp lethality bioassay for cytotoxic activity: Various concentrations of Cocos nucifera L. flower extract were tested for cytotoxicity using the brine shrimp lethality bioassay. The extract increases lethality dose dependently, with 70% mortality at 200 μg/mL, 60% at 100 μg/mL, 50% at 50 μg/mL and 40% at 25 μg/mL. At minimum concentrations (12.5 and 6.25 μg/mL), mortality was 30% and at 3.125 and 1.5625 μg/mL, it decreased to 20%. No lethality was observed at 0.78125 and 0.39063 μg/mL. The LC50 value for the flower extract was calculated to be 40.59 μg/mL, indicating moderate cytotoxicity (Table 3). In comparison, the positive control, vincristine sulfate, resembled an LC50 of 0.544 μg/mL, showing higher cytotoxicity.

Evaluation of anthelmintic activity of Cocos nucifera L. flower extract: The anthelmintic activity of the methanolic extract of Cocos nucifera flower was identified by measuring the time to paralyze and kill at 50 mg/mL (C1SI) and 100 mg/mL (C2SI), using albendazole (25 mg/mL, SSI) concentrations as the standard and vehicle (BSI) as control. As shown in Table 4, the standard drug albendazole significantly caused rapid paralysis (7.3±0.19 min) and death (10.0±0.0 min), compared to the control (p<0.001). Compared to the reference, the methanolic extract at 50 and 100 mg/ml induced paralysis at 42.0±1.38 and 30.0±1.14 min and death at 60.0±0.0 and 63.0±0.0 min, respectively, denoting a notably delayed onset of anthelmintic action relative to the standard.

α-Amylase inhibitory activity of Cocos nucifera flower extract: The α-amylase inhibitory activity of Cocos nucifera flower extract was evaluated at concentrations of 2, 1 and 0.5 mg/mL, using acarbose as a standard reference inhibitor. As shown in Table 5 and 6, the plant extract demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition, with the highest inhibition observed at 2 mg/mL (65.75%), followed by 1 mg/mL (52.05%) and 0.5 mg/mL (33.79%). Based on this trend, the calculated IC50 value for the crude extract was approximately 0.94 μg/mL, indicating moderate inhibitory potency.

In comparison, acarbose exhibited consistent inhibitory effects, with 58.90, 40.64 and 24.66% inhibition at 2, 1 and 0.5 μg/mL, respectively. The corresponding IC50 value for acarbose was calculated to be 1.51 μg/mL. Notably, the plant extract demonstrated superior α-amylase inhibitory activity compared to acarbose, as evidenced by its lower IC50 value.

DISCUSSION

The study assessed the phytochemical composition and pharmacological properties of Cocos nucifera L. flowers, a neglected part of the coconut palm, which has potential therapeutic use. Analysis reveals the presence of different bioactive compounds, including alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins and reducing sugars, which collectively contribute to the observed pharmacological activities. These findings confirm the therapeutic potential of Cocos nucifera flowers, particularly in the context of antioxidant, antidiabetic and cytotoxic effects, making a significant contribution to the existing body of research on this plant.

The preliminary phytochemical analysis of Cocos nucifera (CN) flowers evaluated alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins and reducing sugars, which are known for their antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. These findings support previous studies that highlight the therapeutic potential of Cocos nucifera plants, Selvakumar et al.28, confirmed similar compounds in the roots. Alkaloids and flavonoids may contribute to the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities, while tannins and saponins are recognised for their ability to scavenge free radicals and reduce oxidative stress. The antimicrobial activity observed in this study supports ethnomedicinal claims of Cocos nucifera flowers being used in treating infections, though differences in efficacy between plant parts and solvents suggest further investigation is needed. Cocos nucifera L. flowers have a high gallic acid equivalent (GAE), revealing a significant concentration of phenolic compounds, with an average of 25.629 mg/g (Table 2) and a standard deviation of 1.167. The calibration curve (Fig.1) demonstrated a strong linear correlation (R² = 0.998), supporting the reliability of the results. These findings are in line with Selvakumar et al.28 who also reported significant phenolic content in Cocos nucifera extracts, although their study focused on the roots rather than the flowers. This confirms the potential of Cocos nucifera flowers as a natural source of antioxidants, although further studies are needed to evaluate.

Cocos nucifera L. flowers, assessed by ferric to ferrous reduction activity, demonstrated moderate antioxidant potential (Fig. 2). Higher concentrations (200 and 100 μg/mL) showed absorbance values comparable to the standard, whereas lower concentrations (50 to 6.25 μg/mL) indicated moderate antioxidant properties. These results are consistent with a study29, reported significant antioxidant activity in Cocos nucifera extracts, including tannins and flavonoids. This study found lower reducing capacity than other types; however, it supports the potential of Cocos nucifera flowers as a natural source of antioxidants.

Cocos nucifera L. flower extract showed a dose-dependent increase in inhibition, reaching approximately 80% at the highest concentration, similar to ascorbic acid (Fig. 3). Ascorbic acid inhibited more at lower concentrations, though the flower extract still shows antioxidant activity. These findings are consistent29, reporting strong antioxidant activity in Cocos nucifera extracts from other parts of the plant, particularly husk fibers.

The cytotoxicity of Cocos nucifera L. flower extract showed a dose-dependent increase in mortality, with an LC50 of 40.59 μg/mL (Table 3). At higher concentrations, mortality reached 70%, similar to other plant extracts. In comparison30, reported no significant cytotoxicity at concentrations of 100 and 200 μg/mL for Cocos nucifera extracts from leaf and sheath, indicating potential variability in cytotoxic effects depending on the plant part and solvent used. The moderate cytotoxicity observed in this study suggests that Cocos nucifera flowers could have therapeutic potential, although vincristine sulfate (positive control) showed much higher cytotoxicity.

The anthelmintic activity of Cocos nucifera L. flower extract was evaluated by the time taken for paralysis and death of worms, with the extract showing dose-dependent effects. At 50 mg/mL (C1SI) and 100 mg/mL (C2SI), the extract induced paralysis after 42.0±1.38 and 30.0±1.14 min and death after 60.0±0.0 and 63.0±0.0 min, respectively. In comparison, albendazole (25 mg/mL) induced paralysis in 7.3±0.19 min and death in 10.0±0.0 min (p<0.001). These results are consistent with a previous study by Oliveira et al.31, moderate anthelmintic activity in Cocos nucifera extracts, although the flower extract in this study was significantly slower in action than albendazole. This suggests its efficacy is lower compared to synthetic anthelmintics.

The α-amylase inhibitory activity of Cocos nucifera L. flower extract exhibited a clear dose-dependent response, with the highest inhibition observed at 2 mg/mL (65.75%), followed by 1 mg/mL (52.05%) and 0.5 mg/mL (33.79%) (Table 6). The calculated IC50 value for the extract was approximately 0.94 μg/mL, indicating moderate inhibitory potency. In comparison, acarbose demonstrated consistent inhibitory effects across the tested concentrations, achieving 58.90, 40.64 and 24.66% inhibition at 2, 1 and 0.5 μg/mL, respectively, with an IC50 of 1.51 μg/mL (Table 5). These results suggest that the C. nucifera flower extract exhibits a slightly stronger α-amylase inhibitory activity than acarbose under the conditions tested. Similar irregular patterns were indicate2,31 that while the extract shows promise as an α-amylase inhibitor, further investigation is needed to optimize its dose-dependent behavior and confirm its antidiabetic potential.

CONCLUSION

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the phytochemical composition and pharmacological properties of Cocos nucifera L. flowers. The presence of bioactive compounds, including alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins and reducing sugars, highlights their potential as natural therapeutic agents with antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. The moderate cytotoxic and α-amylase inhibitory effects indicate potential for developing natural anticancer and antidiabetic agents, whereas the anthelmintic activity appears less potent, warranting further investigation. Overall, these findings contribute novel insights into the largely unexplored medicinal properties of coconut flowers and emphasize the need for in vivo and clinical studies to validate their efficacy.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The rising prevalence of oxidative stress-related disorders, diabetes and microbial infections necessitates new natural therapeutic agents. Despite traditional use, Cocos nucifera L. flowers remain pharmacologically underexplored. This study demonstrates significant antioxidant activity, moderate cytotoxicity (LC50 = 40.59 μg/mL) and notable α-amylase inhibition (65.75% at 0.5 mg/mL), along with key phytochemicals such as flavonoids, tannins and alkaloids. These findings identify coconut flowers as a promising source of bioactive compounds, laying the foundation for phytochemical isolation, in vivo studies and potential development of plant-based therapies for metabolic and oxidative stress-related disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to express my gratitude to my department for their support and to the National Herbarium of Bangladesh, Mirpur, Dhaka, for their assistance with the plant taxonomy. I am also grateful to my teachers and friends for their unconditional help in acquiring materials as well as completing the research on time. I acknowledge that I have received no funds or financial aid for this research.

REFERENCES

- Cragg, G.M. and D.J. Newman, 2013. Natural products: A continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj., 1830: 3670-3695.

- DebMandal, M. and S. Mandal, 2011. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.: Arecaceae): In health promotion and disease prevention. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med., 4: 241-247.

- Lima, E.B.C., C.N.S. Sousa, L.N. Meneses, N.C. Ximenes and M.A. Santos Jr. et al., 2015. Cocos nucifera (L.) (Arecaceae): A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res., 48: 953-964.

- Kalina, S. and S.B. Navaratne, 2019. Analysis of antioxidant activity and texture profile of tender-young and king coconut (Cocos nucifera) mesocarps under different treatments and the possibility to develop a food product. Int. J. Food Sci., 2019.

- Vinod, N.P. and D.J. Rani, 2024. Anti inflammatory and anti diabetic activity of Cocos nucifera inflorescence. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. Sci., 10: 11-16.

- Liu, H., N. Qiu, H. Ding and R. Yao, 2008. Polyphenols contents and antioxidant capacity of 68 Chinese herbals suitable for medical or food uses. Food Res. Int., 41: 363-370.

- Liu, R.H., 2003. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 78: 517S-520S.

- Renjith, R.S., A.M. Chikku and T. Rajamohan, 2013. Cytoprotective, antihyperglycemic and phytochemical properties of Cocos nucifera (L.) inflorescence. Asia Pac. J. Trop. Med., 6: 804-810.

- Linde, J., S. Combrinck, S. van Vuuren, J. van Rooy, A. Ludwiczuk and N. Mokgalaka, 2016. Volatile constituents and antimicrobial activities of nine South African liverwort species. Phytochem. Lett., 16: 61-69.

- Vadivu, C.C., M. Palanisamy, A. Devi, V. Balakrishnan and T. Sundari, 2020. Phytochemical, antimicrobial and antioxidant studies of Cocos nucifera (L.) flowers. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 6: 337-343.

- Kannaian, U.P.N., J.B. Edwin, V. Rajagopal, S.N. Shankar and B. Srinivasan, 2020. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of coconut cotyledon. Heliyon, 6.

- WHO, 2019. WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, ISBN: 9789241515436, Pages: 226.

- Akram, M. and A. Nawaz, 2017. Effects of medicinal plants on Alzheimer's disease and memory deficits. Neural Regener. Res., 12: 660-670.

- Mollik, M.A.H., M.S. Hossan, A.K. Paul, M. Taufiq-Ur-Rahman, R. Jahan and M. Rahmatullah, 2010. A comparative analysis of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal healers in three districts of Bangladesh and inquiry as to mode of selection of medicinal plants. Ethnobot. Res. Applic., 8: 195-218.

- Gupta, A., M. Naraniwal and V. Kothari, 2012. Modern extraction methods for preparation of bioactive plant extracts. Int. J. Appl. Nat. Sci., 1: 8-26.

- Zygler, A., M. Słomińska and J. Namieśnik, 2012. Soxhlet Extraction and New Developments Such as Soxtec. In: Comprehensive Sampling and Sample Preparation: Analytical Techniques for Scientists, Pawliszyn, J. (Ed.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-0-12-381374-9, pp: 65-82.

- Edeoga, H.O., D.E. Okwu and B.O. Mbaebie, 2005. Phytochemical constituents of some Nigerian medicinal plants. Afr. J. Biotechnol., 4: 685-688.

- Chhabra, S.C., F.C. Uiso and E.N. Mshiu, 1984. Phytochemical screening of Tanzanian medicinal plants. I. J. Ethnopharmacol., 11: 157-179.

- Evans, W.C. and D. Evans, 2009. Phenols and Phenolic Glycosides. In: Trease and Evans' Pharmacognosy, Evans, W.C. and D. Evans (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-0-7020-2933-2, pp: 219-262.

- Glick, D., 1968. Methods of Biochemical Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New Jersey, ISBN: 9780470110348, Pages: 446.

- Lieberman, M., 1999. A brine shrimp bioassay for measuring toxicity and remediation of chemicals. J. Chem. Educ., 76.

- Solis, P.N., C.W. Wright, M.M. Anderson, M.P. Gupta and J.D. Phillipson, 1993. A microwell cytotoxicity assay using Artemia salina (brine shrimp). Planta Med., 59: 250-252.

- Ajaiyeoba, E.O., P.A. Onocha and O.T. Olarenwaju, 2001. In vitro anthelmintic properties of Buchholzia coriaceae and Gynandropsis gynandra extracts. Pharm. Biol., 39: 217-220.

- Argal, A. and A.K. Pathak, 2006. CNS activity of Calotropis gigantea roots. J. Ethnopharmacol., 106: 142-145.

- Aidoo, D.B., D. Konja, I.T. Henneh and M. Ekor, 2021. Protective effect of bergapten against human erythrocyte hemolysis and protein denaturation in vitro. Int. J. Inflammation, 2021.

- Alqahtani, A.S., S. Hidayathulla, M.T. Rehman, A.A. ElGamal and S. Al-Massarani et al., 2020. Alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase enzyme inhibition and antioxidant potential of 3-oxolupenal and katononic acid isolated from Nuxia oppositifolia. Biomolecules, 10.

- Ali, H., P.J. Houghton and A. Soumyanath, 2006. α-Amylase inhibitory activity of some Malaysian plants used to treat diabetes; with particular reference to Phyllanthus amarus. J. Ethnopharmacol., 107: 449-455.

- Selvakumar, P., M.D. Kanniyakumari and V. Loganathan, 2016. Phytochemical screening and in vitro antioxidant activity of male and female flowers ethanolic extracts of Cocos nucifera. Int. J. Life Sci., 5: 127-131.

- Silva, R.R., D.O.E. Silva, H.R. Fontes, C.S. Alviano, P.D. Fernandes and D.S. Alviano, 2013. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of Cocos nucifera var. typica. BMC Complementary Altern. Med., 13.

- do Nascimento Tavares Figueira, C., J.M. dos Santos, F.T.X. Póvoas, M.D.M. Viana and M.S.A. Moreira, 2016. Assessment of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of crude extracts from Cocos nucifera Linn. J. Chem. Pharm. Res., 8: 276-282.

- Oliveira, L.M.B., C.M.L. Bevilaqua, C.T.C. Costa, I.T.F. Macedo and R.S. Barros et al., 2009. Anthelmintic activity of Cocos nucifera L. against sheep gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet. Parasitol., 159: 55-59.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Al-Amin, Aktar,

M.J., Hossain,

N., Siddiq,

M.M., Akter,

J., Kuddus,

M.R., Rashid,

M.A. (2026). Pharmacological Potential of Cocos nucifera L. Flowers: Phytochemical, Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Anthelmintic and Anti-Diabetic Insights. Asian Journal of Biological Sciences, 19(1), 40-50. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2026.40.50

ACS Style

Al-Amin; Aktar,

M.J.; Hossain,

N.; Siddiq,

M.M.; Akter,

J.; Kuddus,

M.R.; Rashid,

M.A. Pharmacological Potential of Cocos nucifera L. Flowers: Phytochemical, Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Anthelmintic and Anti-Diabetic Insights. Asian J. Biol. Sci 2026, 19, 40-50. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2026.40.50

AMA Style

Al-Amin, Aktar

MJ, Hossain

N, Siddiq

MM, Akter

J, Kuddus

MR, Rashid

MA. Pharmacological Potential of Cocos nucifera L. Flowers: Phytochemical, Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Anthelmintic and Anti-Diabetic Insights. Asian Journal of Biological Sciences. 2026; 19(1): 40-50. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2026.40.50

Chicago/Turabian Style

Al-Amin, Mst. Jesmin Aktar, Nazmul Hossain, Md Mahfuj Alam Siddiq, Jeasmin Akter, Md Ruhul Kuddus, and Mohammad A. Rashid.

2026. "Pharmacological Potential of Cocos nucifera L. Flowers: Phytochemical, Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Anthelmintic and Anti-Diabetic Insights" Asian Journal of Biological Sciences 19, no. 1: 40-50. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2026.40.50

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.